Muneefist Destiny, Alfred Quiroz. Collection of the artist. Photo courtesy of the artist.

The vibrancy and urgency of Mexican American visual art and the Chicano Civil Rights Movement take centre stage at the Museum of Anthropology (MOA)’s latest exhibition Xicanx: Dreamers + Changemakers / Soñadores + creadores del cambio, running until January 1, 2023.

The exciting project, three years in the making, is the product of a collaboration between co-curators Jill Baird, MOA Curator of Education, and Greta de León, Executive Director of The Americas Research Network. “To find common threads and to be able to find really interesting notes of discussion about the whole movement and the artists and the works was a really exciting experience,” says de León.

Greta de León

The exhibition focuses on artists of Mexican American heritage, who self-identify as Xicanx (pronounced chi-can-x), which is the gender neutral, inclusive version of Chicano/a and which also invokes the Indigenous roots of the artists. “For me, the most important thing is to showcase the enormous diversity Xicanx artists have, how vibrant their work is,” de León says.

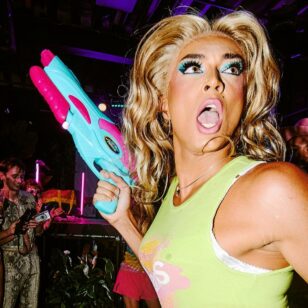

Xicanx: Dreamers + Changemakers features work by 33 Mexican American artists from across the United States, including New York, Texas, and New Mexico. The bright colours of the exhibition walls mirror the energy of the artwork, which ranges from a projected visual documentary of murals that fight against inequality, to a mixed media map (Muneefist Destiny by Alfred J. Quiroz) of what was once Mexico before American jingoistic expansion. The mediums used, such as paintings, prints, sculpture, and a game (Loteria), are diverse, as are the content and aesthetics of the pieces. However, two commonalities do emerge: a willingness to speak out against injustice and oppression as well as fervent persistence of identity.

La Güera, Ana Hernández. Private collection. Photo courtesy of the artist.

For de León, art and activism are entwined for Xicanx creatives. “Chicano is an identity so you have to work on it. You become a Chicano. You’re not born a Chicano. It implies a commitment. It implies an activism. And when you’re an artist, your art is always marked with that,” she says. In short, “you can’t have Chicano art without the activism.”

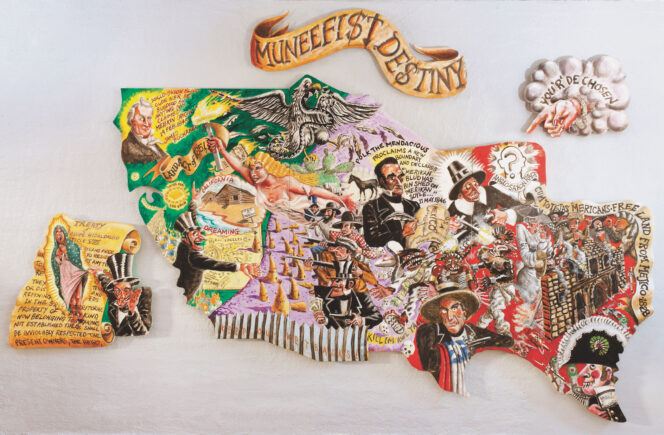

The artwork spans the 1970s, roughly the beginnings of El Movimiento, the Chicano Civil Rights Movement, to 2022. The pieces speak of discriminatory immigration practices, alienation within America, labour injustices, police violence, and the hopes and dreams of those migrating to a new home. For example, Rudy Treviño’s Lettuce Field with Target and Skull viscerally captures the plight of farmworkers whose bodies are used for their labour, and who are thwarted in their efforts to unionize in protest against their mistreatment.

Lettuce Field with Target and Skull, Rudy Trevino. Collection of the artist. Photo

courtesy of the artist.

One particularly powerful work is an installation Altar for the Spirit of Rasquachismo: Homenaje a Tomás Ybarra Frausto by David Zamora Casas, which reimagines the Day of the Dead traditions in order to explore Xicanx identity. Melding a variety of cultural and religious iconography and a spoken-word video, it challenges terms—many derogatory—that have assigned to Mexican Americans and instead explores “Rasquachismo,” a term coined by Tomás Ybarra Frausto that celebrates working class and mixed artistic expressions. “The Xicanx have to create their own identity, being rejected by Mexican nationalists and being rejected by U.S. citizens. It’s really an enormous work of resilience being colonized twice—or three times,” de León says.

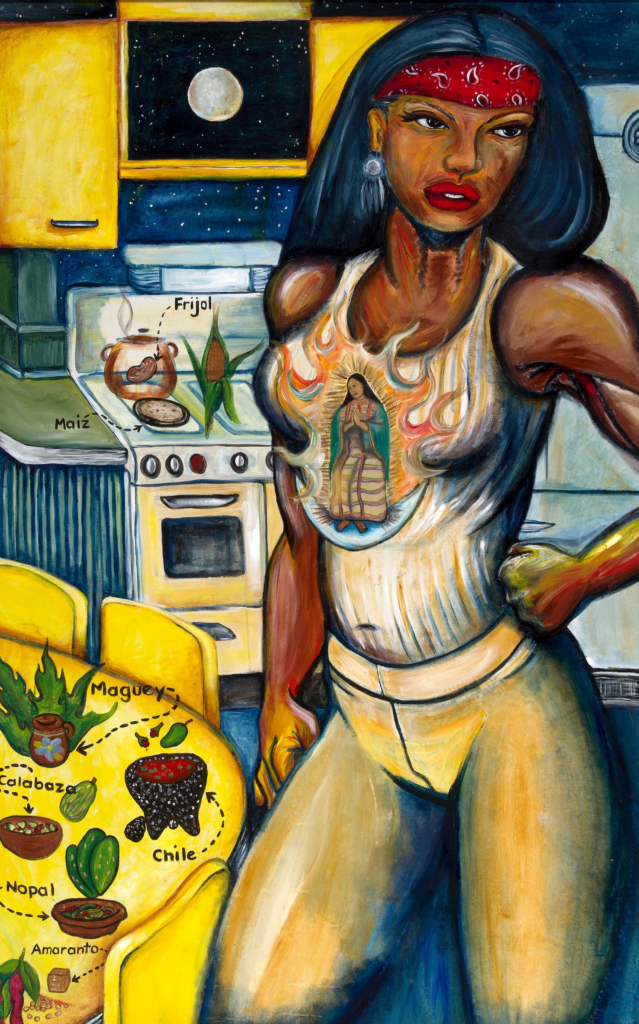

Through this exhibition, the borderland identity of Xicanx artist is revealed to be incredibly rich—and evolving over generations. Firstly, for de León, it is about locating artists who identify as Chicano. Then, it’s about showcasing not only iconic figures from the early days of Chicano art, but also more contemporary creators, such as female, non-binary, and queer artists who are going beyond the movement’s macho roots. “It’s really exciting to see how the movement is very vital and essential. The struggle continues,” she says. De León is struck by works that confront the representation of women. A beautiful red embroidered dress by Sarah Castillo (Embroidered Tears) explores female physicality, violence, and self-forgiveness.

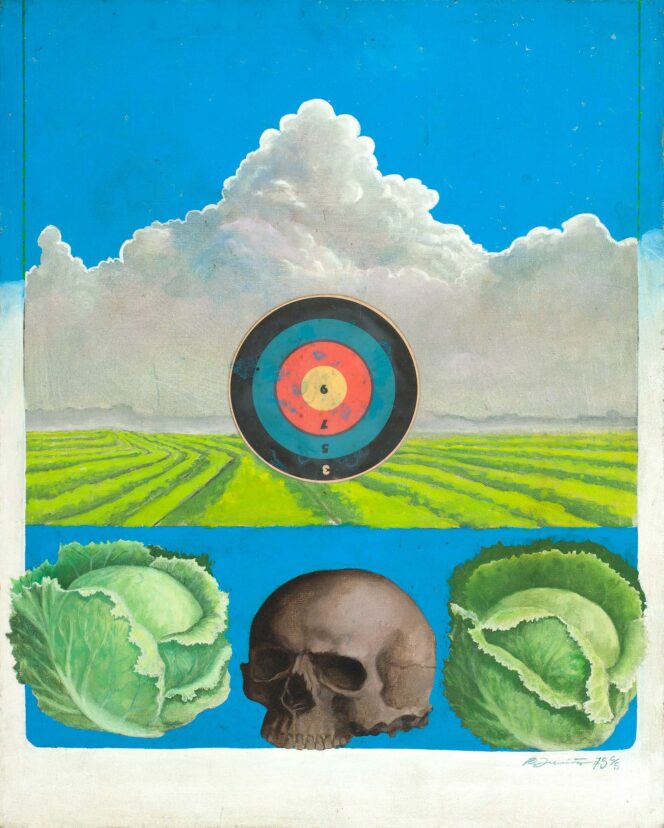

Citlali: Cuando Eramos Sanos, Debora Kuetzpal Vazquez. Collection of the artist.

Photo courtesy of the artist.

In addition to visual elements, in a range of mediums, language also figures prominently in the exhibition. Spanish and English coexist in the overall title as well as in descriptions and labels. De León underlines that it is important that the way the artists write about themselves is respected. In many cases, they are fluent in Spanglish, a hybrid of the two languages.

Quotes from writers and poets appear on the walls of the exhibition, such as a line by Gloria E. Anzaldúa: “this is my home / this thin edge of / barbwire.”

The exhibition, with its themes of social justice and public art, is an ideal fit for Vancouver, which has a long tradition of activism as well as art in the public realm (e.g., the Vancouver Mural Festival). De León is incredibly happy that the exhibition is being presented in this city, with its vibrant Latin American communities. When she came here to view the exhibition, she encountered many visitors who found the exhibition spoke to them. “There are a lot of Latin Americans in Vancouver so to have an exhibit that is in Spanish and could represent or mirror some of their realities is pretty cool,” she says.

De León says the exhibit is well suited to the MOA in Vancouver since it is about a diverse community expressing itself in so many different ways. “Our exhibit is not didactic. It’s an art exhibit about the political movement. And it’s about the whole cultural tradition of Chicano art,” she says. Xicanx Digital expands the scope of the exhibition by including cuisine, film, music, and literature.

De León is modest about her role as co-curator with Jill Baird, shifting the spotlight to the artists themselves. “What we’re doing is basically holding the microphone for Chicano artists and activists to speak. We’re just the set crew organizing the set for them to showcase their struggle, and their beautiful work,” she says.

For further information on the exhibition, visit the MOA website.